This dialog contains the full navigation menu for this site.

When Cassandra Miller-Butterworth was a teenager, she spent the summer laboring alongside a veterinarian from her hometown in South Africa. She had always loved animals and wanted to test her dream of working with wildlife.

The vet, a small and farm animal specialist, was impressed with her knowledge, her work ethic and her passion. But, still, as the summer came to its inevitable close, he offered Miller-Butterworth a kind warning.

“I think you’d be an excellent vet, but you’re going to struggle because you’re a woman,” he told her. Her petite frame didn’t help. The farmers, he predicted, would never trust her to wrestle with a horse or cow.

“The farmers will laugh at you,” he said.

“He was right,” Miller-Butterworth said. “I didn’t take offense at all. He was being very realistic.”

So when Miller-Butterworth went off to study at the University of Cape Town, she chose zoology as her major.

Three decades later, South Africa has changed. Women now outnumber men in veterinary schools and many have taken jobs in large animal or wildlife medicine.

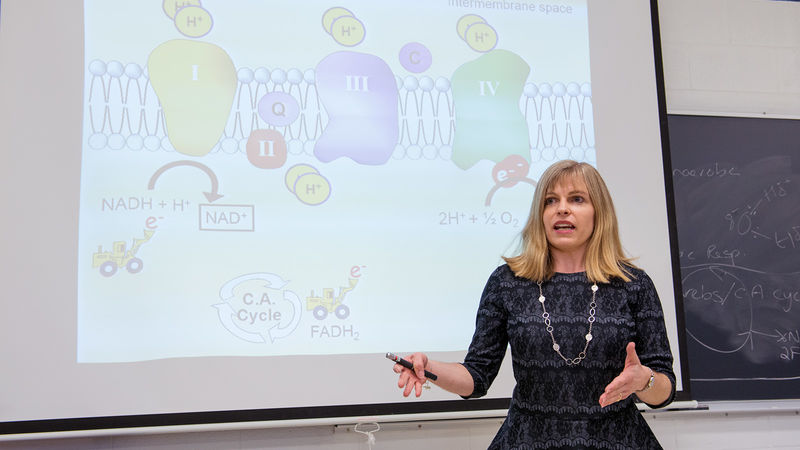

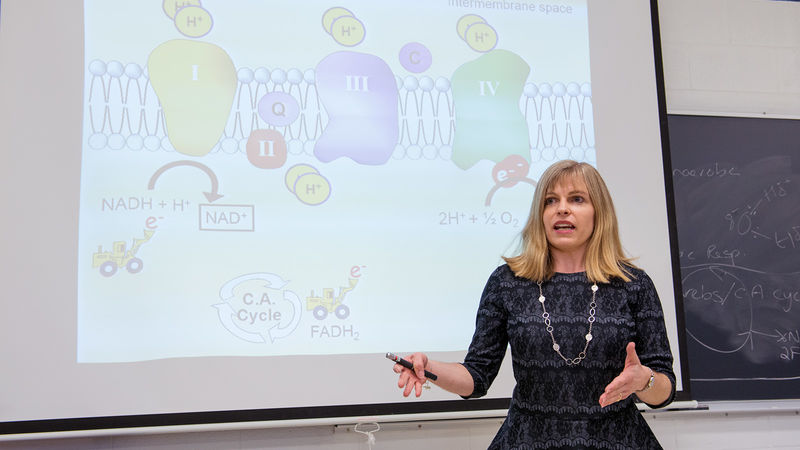

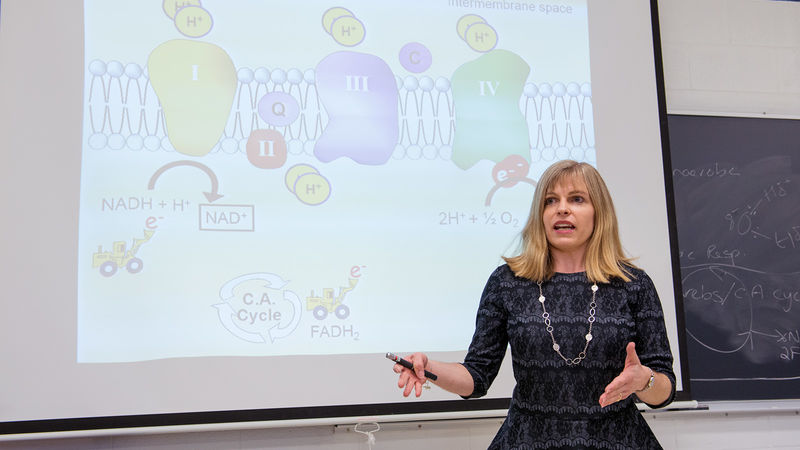

In the United States, Miller-Butterworth has witnessed a similar shift in science, technology, engineering and math. About half of the students in her biology classes at Penn State Beaver are female, and laboratory jobs nationwide are increasingly filled by women.

On the Beaver campus, Miller-Butterworth is one of seven female STEM professors. That’s half of all STEM professors on campus, much better than the national average.

But even those promising statistics can’t mask the larger problem — females are still underrepresented in STEM fields.

According to the U.S. Department of Commerce, women hold a disproportionately smaller share of STEM undergraduate degrees, particularly in engineering. And while women comprise half of the country’s workforce, only a quarter of the jobs in STEM belong to women.

To Cheryl Moon-Sirianni, a civil engineer and a member of the Penn State Beaver Advisory Board, that’s not just disheartening, it’s a call to action.

“To me, it’s terrible,” Moon-Sirianni said. “There are not enough people reaching out to young women and encouraging them, and it has to start young. A lot of girls don’t think they can go into it; someone needs to tell them they can.”

When Penn State Beaver's Sherry Kratsas, an instructor in engineering and computer science, was young, she wanted to be everything. At one point she even considered marine biology, an odd choice for a girl growing up in landlocked Philippi, West Virginia.

That she eventually decided on engineering wasn’t really a surprise. Her dad was a heavy equipment mechanic and she often served as his assistant. Saturday mornings went something like this: Paint. Patch the boat. Fetch the tools. Change the brakes and drop a new engine into the car.

There was nothing she couldn’t — or wouldn’t — do.

So when she stepped into her engineering classes at West Virginia University and was one of the only females in the room, she wasn’t much bothered by it.

“I knew I was a minority and expected to be,” she said. “I wasn’t afraid to compete with men. My dad and brother made me a little competitive.”

Research shows that role models like Kratsas’ father help to break down stereotypes and allow girls to see that there is a place for them in STEM. The call for role models is so strong that even the White House joined the cry, producing a series of Google Hangouts called “We the Geeks” that highlight science, technology and innovation in the U.S. Several focused directly on STEM innovators and the examples they set for girls.

The problem, according to Moon-Sirianni, is that too few of those STEM role models are female.

As an assistant district executive for design at the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation, Moon-Sirianni does a lot of hiring. More than 90 percent of the applicants are men. And she always asks the same question: “What made you want to be an engineer?”

At this point, the answers are pretty predictable. My dad was an engineer. My uncle was in construction. I liked Tonka trucks.

“I’ve never had someone come in and say ‘my mom was an engineer,’ ” Moon-Sirianni laments. “Engineering is an industry dominated by men.”

In science, particularly biology, female role models seem to be in better supply. Beaver Biology Instructor Stephanie Cabarcas-Petroski was a graduate student at St. John’s University in New York when she joined the molecular biology lab of her future mentor Laura Schramm.

“I’ve never had someone come in and say ‘my mom was an engineer.’ Engineering is an industry dominated by men.” Cheryl Moon-Sirianni, civil engineer

At the time, Schramm, now an associate professor and associate dean at St. John’s, didn’t have the protection of tenure, so working in her lab was considered a gamble. Cabarcas-Petroski happily took it. She wanted the guidance of a young female faculty member, and Schramm’s focus on the transcription of cancer cells interested her; her grandmother had died of cancer when she was just four years old.

While they worked together, Schramm gave birth to two children, excelled at research and earned tenure.

“She was the definition of superwoman to me,” Cabarcas-Petroski said. “It was amazing to watch a woman in a male-dominated department go through that process.”

That experience prompted Cabarcas-Petroski to take a post-doctoral fellowship at the National Cancer Institute in Frederick, Maryland, where she was able to continue cancer research.

Though she has since traded the lab for the classroom, Cabarcas-Petroski still looks to Schramm as a mentor and collaborator. The pair has published together, including a recent paper about breast cancer and the consumption of soy products.

Perhaps because of her relationship with Schramm, Cabarcas-Petroski is keenly aware of the way that young, female students may view and emulate her. She begins each semester by explaining her background in research. She wants her students, particularly the young women, to understand what’s possible in biology.

“When you feel you’re in it alone, it’s harder to make progress,” she said.

The nation’s focus on women in STEM, or lack thereof, has led many educators to take a deep-dive look at what attracts and retains females in those fields. What they’ve found can be simplified and summed up in three words: women like results.

Lina Nilsson, the innovation director at the Blum Center for Developing Economies at the University of California, Berkeley, recently penned an article for The New York Times suggesting women are drawn to engineering projects that produce some societal good.

And an article in Inside Higher Ed posited that female STEM students have better outcomes when they study in a project-based curriculum.

The idea is that women are more likely to thrive when they can see the outcome of their work.

If those theories are correct, Penn State Beaver professors are ahead of the curve. Instructors in all disciplines, but particularly in STEM, have increasingly been taking learning beyond the classroom, assigning semester-long, curriculum-based projects that bring lectures to life.

Last year, Miller-Butterworth and Cabarcas-Petroski asked their biology students to research and design bat houses for the campus, an effort to ease the deadly effects of white nose syndrome by giving female bats safe places to roost with their pups.

Faculty members Cassandra Miller-Butterworth, left, and Stephanie Cabarcas-Petroski, right, examine a bat house made by a group of engineering students.

Last spring, Mathematics Instructor Angela Fishman had her sustainability students create and build permanent, environmentally friendly fixtures for the campus community, including a composting site and a straw bale garden.

Information Sciences and Technology Instructor Amber McConahy and her students teamed with electrical component company c3 controls in a yearlong effort to build a new online purchasing system for its customers.

And each semester in Engineering Design 100, Kratsas and Senior Engineering Instructor Jim Hendrickson pair their students with real-world clients to work on semester-long projects.

This spring, one of those projects called for students to design a new smoke machine for the Pine Run Fire Department so firefighters are better able to train for zero-visibility situations. Jordan Devault is the team lead — one of two female team leads in the class.

It’s just her second semester in the engineering program, but she’s already become accustomed to being the only female, or only other female, in her classes. And she doesn’t mind, as she calls it, “leading the guys.” As she sees it, she’s more organized than the rest of her teammates, which made her a natural fit to steer the group. Plus, she looks at the project from a different perspective than they do.

“The goal isn’t to have a working machine,” she said. “It sounds funny, but I think that’s not really the point. The point is to learn that you’re going to have setbacks, learn how to take customer comments and learn how a team works.”

In other words, she’s taking a long view of her education, her sights clearly set on her ultimate career goal, knowing that each project she leads, each team she collaborates with, is another step on her way to breaking the glass ceiling hovering above her.

Because that ultimate career goal is to become an audio engineer in the music industry, a job traditionally dominated by men.

In 1990, when Fishman received her doctorate in engineering from Wichita State University, she made history as the first woman to graduate from the engineering college with a doctorate.

Because her specialty was in reliability, and reliability experts are always in high demand, she never had trouble finding a job. In fact, she worked on some of the industry’s most cutting edge projects, including the military’s Apache helicopter and General Motors’ first electric car.

It was challenging and exhilarating, and sometimes frustrating, because Fishman knew, though the quality and importance of her work was equal to her male counterparts, her pay was not.

“I had to learn how to play the game,” she said. “I had to learn how to toot my own horn.”

It’s a skill she encouraged female students to hone when she headed Penn State Beaver’s Center for Academic Achievement and mentored young women interested in STEM disciplines. She received a Penn State Women in Science and Engineering Award for her efforts.

And it’s a skill many women in the working world still need to perfect, according to Moon-Sirianni. And because media and politics are increasingly focusing on women’s rights — including equal pay and maternity leave — she believes the opportunities for women to shine in the male-dominated world of STEM have never been greater.

“I don’t think a lot of girls know the opportunities for advancement,” Moon-Sirianni said. “We want to promote women (at PennDOT).”

It’s a lesson she imparts when she speaks to girls and young engineers, which she does often, and encourages her employees to do, too.

When her daughter was a student at North Allegheny High School, for example, Moon-Sirianni was a frequent guest in the classroom, touting the benefits that come with an engineering career — team-based work, job stability, the chance to stand out in a sea of men.

“Why would you want to be one of 1,000 in nursing when you could stand out and have so much opportunity to be noticed in engineering?” she’d ask them.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Moon-Sirianni’s daughter is now a freshman industrial engineering major at University Park, and many of her friends chose STEM majors, as well.

That was the upshot of a few visits to a local high school. Imagine if all women in STEM committed to reaching out to young girls, said Moon-Sirianni.

“There so much potential,” she said. “There’s nobody else guiding them. We need to do it.”